Coronavirus and Employment Law: What Should Employers and Employees Know?

*NOTE: This article addresses the application of existing laws to the coronavirus pandemic. For a discussion of new requirements under the recently enacted Family First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA), which expands the requirements of the FMLA and FLSA, see Part 2 of this article.

In light of the outbreak of coronavirus, which is currently having a significant impact on the operations of many businesses, it is important for both employers and employees to be mindful of their legal rights and obligations. The following is a summary of some of the key legal issues that might arise under pertinent employment statutes:

Family and Medical Leave Act

⦁ An employee who tests positive for coronavirus would unquestionably have a serious health condition under the FMLA. Assuming that employee meets the other criteria for coverage (12 months service, 1,250 hours worked within previous 12 months, employed at a location with 50 or more employees within a 75 mile radius),, the employee should be placed on FMLA leave.

⦁ If the business continues to operate while the employee is out, the employer may count the time off towards the employee’s 12 week allotment of protected leave. However, if the business shuts down or otherwise furloughs its employees for any period of time, that time cannot be counted towards the employee’s allotment of leave.

⦁ An employer may require a fitness for duty certification prior to permitting an employee who has contracted coronavirus from returning to work.

⦁ Refusal to reinstate an employee who has recovered from the virus could prompt claims for interference with rights and retaliation under the FMLA.

Americans with Disabilities Act

⦁ Although coronavirus is a temporary condition that does not meet the definition of “disability” under the ADA, the law might nonetheless be implicated if an employer unreasonably refuses to reinstate an employee who has recovered from the virus.

⦁ An employer’s refusal to reinstate or dismissal of an employee who has recovered from the virus could be deemed as discrimination against someone who is “regarded as” having a disability.

⦁ Conversely, temporary measures short of dismissal (i.e. mandatory leave) for individuals known or suspected to have been exposed to the virus would likely be deemed permissible, given the legitimate need to protect co-workers from exposure.

⦁ Because coronavirus is not a “disability,” the ADA does not require that employers accommodate those with the virus by permitting telecommuting or work from home. If employers elect to do so, however, they may set a precedent applicable to disabled employees who request the option of working from home in the future.

Fair Labor Standards Act

⦁ Hourly employees will continue to be paid for the hours they work. If employees are working from home or remotely due to “social distancing” practices, employers should implement clear rules for reporting working hours to ensure that all hours are paid and that employees are not over-reporting their time.

⦁ Salaried exempt employees who miss time because they have contracted the virus are generally not entitled to pay under the FLSA. The employer may pro-rate salaries (for partial week absences after PTO is exhausted) or suspend salary payments (for full week absences) while the employee is out of work without destroying the salary basis of pay.

⦁ If the employer shuts down the business, salaried employees are entitled to their full salary for any partial week worked (i.e. if the employer shuts down or re-opens the business mid-week). No salary is due during any full week in which no work is performed.

⦁ Salaried nonexempt employees paid pursuant to a fluctuating workweek pay plan should receive their full salary in any week in which any work is performed.

Workers Compensation

As coronavirus, even if arguably contracted through work interactions, is not “workplace illness” (compared to, for example, “black lung” in coal miners), and therefore would likely be deemed outside of workers compensation coverage.

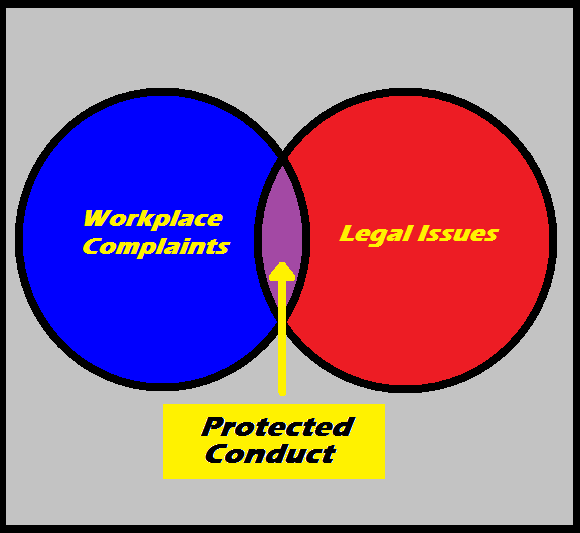

Compelled Attendance

The biggest grey area in the law arises from the question of whether employers may compel employees to work or, stated another way, terminate those who refuse to come to work, during the outbreak.

In an at-will state such as Florida, employers can, of course, terminate employees for any reason. Certainly, a refusal to work qualifies.

An ancillary question is whether an employee who is compelled to work and then contracts the virus might have a claim against the employer under a theory of negligence. While courts have rejected claims of this type in the past (i.e. Quezada v Circle K Stores, Inc., 18 Fla. L. Weekly Fed. D 795 (M.D. Fla. 2005)), the law remains somewhat unsettled in this area.

Conclusion

Ultimately, employers must work with employees to balance their respective interests and avoid the legal pitfalls that might arise. Our firm remains available to address specific questions in this area, and will remain accessible throughout this crisis. Stay safe and stay healthy!